Battling my Cultural Identity (1652)

Although I am Salvadoran, I have always felt disconnected from the culture. I only feel half Salvadoran because I was not brought up immersed in the culture, nor have I learned about my heritage and important aspects of Salvadoran history. I never had a quinceñera like my cousins or learned traditional steps to dance at parties. During these moments, I tend to experience racial imposter syndrome (RIS) which, like imposter syndrome, is a “psychological pattern of behavior wherein people (even those with adequate external evidence of success) doubt their abilities and have a persistent fear of being exposed as a fraud” (Lacey).

RIS is difficult to define because it cannot simply be described as one set thing and universal experience; instead, its meaning changes depending on one’s own personal and lived experiences (Lacey). In my experience, I have felt RIS during my interactions with the Salvadoran community. Although I have the right to belong, I feel as though I do not, due to disrespect, personal issues, or another aspect. Because of RIS, the importance of my other identifiers, such as gender and sexuality, are overshadowed and scrutinized in the context of my Salvadoran identity. The most salient aspect of my identity as a female identifying, queer individual is my identity as a hybrid, intersectional White and Salvadoran individual; it causes me discomfort when confronting language barriers, responding to questions about my appearance, and experiencing societal backlash due to attempts at categorization.

Gloria Anzaldúa demonstrates the struggles experienced as a person of mixed descent, which leads to inner conflict and discomfort in me because it takes precedence over other things in my life. Gloria Anzaldúa is a writer who has the power of illustrating hybridity in a beautiful way. In her piece, “La Conciencia de la Mestiza: Towards a New Consciousness,” Anzaldúa discusses hybridity and being an individual of mixed race. Hybridity is a mixing of two oppositional binary identities.

It can be described as “riding the hyphen” between two binaries; instead of being Salvadoran or American, I am Salvadoran-American (Buckmire). Racial hybridity is defined as a mixture of races when boundaries are crossed (Lacey). Gloria Anzaldúa beautifully describes the battle that I feel regarding this racial hybridity, writing, “la mestiza undergoes a struggle of flesh, a struggle of borders, an inner war” (Anzaldúa 78). I am la mestiza, constantly struggling to fit in in one community or another. There is a constant “struggle of borders” for me and where I fit in, as I am not White “enough” to be considered Caucasian, but at the same time I am not Salvadoran “enough” to be considered Salvadoran. I do not fit in anywhere, no matter how hard I try. I am constantly facing an “inner war” between these different cultures. Karen Matsuoka writes in her essay titled “Trying to Understand My Japanese-American Identity,” “I never knew how and what words to use to describe this feeling: a feeling of floating in identities but also not being able to feel complete in both of my identities” (Matsuoka). This quote resonates with me as I am, too, navigating multiple cultures and identities. For Matsuoka, “floating” signifies the feeling of changing identities and never settling in one which results in feelings of incompleteness and discomfort. While this struggle is unpleasant, it is also a beauty, and Anzaldúa highlights this version of hybridity, detailing, “I am an act of kneading, of uniting and joining that not only has produced both a creature of darkness and a creature of light, but also a creature that questions the definitions of light and dark and gives them new meanings” (Anzaldúa 380). In this passage, Anzaldúa demonstrates hybridization and the act of being in between two cultures. For Anzaldúa, an individual who identifies as mixed race creates a blend of both cultures, helping to bring them together and creating unique beauty. While explaining the blend, she also remarks how a new person is created from the mixing, a person who is different from the originals and can defy expectations. As Matsuoka and Anzaldúa demonstrate, hybridity is both a beautiful and uncomfortable thing which resonates with me as una mestiza juggling two cultures.

Additionally, the language barrier between Spanish and English sparks discomfort in me because I cannot speak Spanish fluently, which is a significant aspect to racial identity. I feel out of place during family gatherings when the spoken language is mainly Spanish. I cannot understand and therefore I cannot fully participate in the conversation.

https://physio.uwc.ac.za/pht402/2019/05/24/language-barriers/

Gloria Anzaldúa, in her chapter “How To Tame a Wild Tongue,” discusses the connection between language and identity, and writes, “Until I can take pride in my language, I cannot take pride in myself” (Anzaldúa 59). Although Anzaldúa is expressing this thought within the context of having to switch back and forth from Spanish to English, this instead resonates with me because of the fact that I lack bilinguality. The older relatives with more stories speak mostly Spanish, and even though I am trying my best to learn, I cannot communicate with them as much as I would like to. The lack of communication means that important family history and stories are lost to me, and therefore it is difficult to pass them down. This ties back into RIS as I feel that I do not truly belong in my Salvadoran culture as I do not know my stories and the language. The language barrier creates feelings of isolation and questions of self-worth; it tends to make me spiral into questioning my security in my Salvadoran heritage and how “Salvadoran” I am, which brings up many feelings of racial imposter syndrome. The language barrier between cultures is the biggest border in my hybridity, creating distress within my identity.

Appearance is important, as it correlates with one’s treatment and categorization in society; I am uncomfortable when people judge my appearance, which unfortunately happens in a lot of my interactions. In his essay titled “White by Law,’ Haney Lopez describes a case with three women brought before the court in order to determine their race and whether or not they were “free” or enslaved. He writes, “[t]he fate of the women rode upon the complexion of their face, the texture of their hair, and the width of their nose” (Lopez 192). The verdict was based solely on appearance, which demonstrates how dependent society is on physiology to adjudicate race. When a person is of mixed descent, they are considered to be of the race that is considered subaltern by society. For example, when a person is White and Black, they are considered Black, although they are in hybrid and have qualities of both. Their categorization in society is due to their outward appearance, especially their skin color. The One Drop Rule states that if a person has even one drop of “black blood,” they are considered Black (Davis 2014).

https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facbooks/18/

https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facbooks/18/

Society sees skin color in a different way than simply that; instead, people introduce essentialism. The concept of essentialism is the idea that people of an identity group all have an essence that “encapsulates their identity” (Buckmire). This can lead to stereotyping when society believes everyone in a particular group has a certain essence. Stereotyping can be extremely harmful and prevalent in interactions of those of a darker skin tone. My Salvadoran relatives are most, if not all, darker in skin color than me; to me, they are truly Salvadoran, whereas I do not believe that I am. My feelings of alienation within the Salvadoran community leads to thoughts of intrusion. Although skin color may seem like an arbitrary determinant of one’s ethnic identity, this disconnection has always been relevant and apparent to me. These feelings of being an intruder or outsider in my own race lead to discomfort and unease.

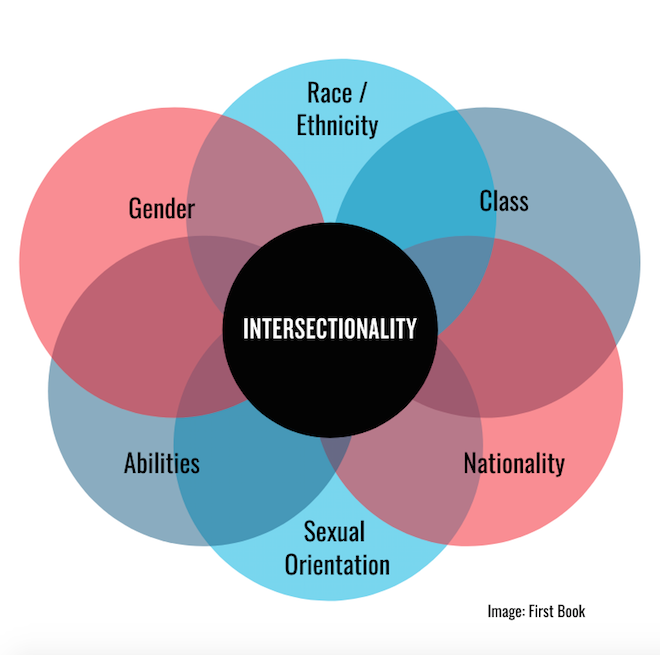

On the other hand, the intersectionality of my various identities (White, Salvadoran, female, queer) leads to uncomfortable situations surrounding Latinx stereotypes and gender expression. Intersectionality dictates that no person can be completely described by any one identity. Instead, people are a mix of various factors that make them unique (Hankivsky, 2).

https://www.namidanecounty.org/blog/2022/3/30/pgsrbl96qsbg05c2ma62img929smff

However, my Salvadoran identity seems to overshadow my other identities, as I am seen through a Latinx lens. I identify as a female, and therefore meaning that I am subjected to stereotypes relating to Latinx women. For example, society assumes that Latinx women are house cleaners, maids, and cooks, consequentially viewing them as lesser than males. Another thing I deal with is my Salvadoran identity in relation to my sexuality. I often feel out of place at Salvadoran and Latinx events because I do not feel as feminine as the women there express themselves in their makeup, high heels, and dresses. Moreover, this feeling sometimes conflicts with my sexual identity and gender expression, as I sometimes feel more masculine and want to dress in baggier clothing, resulting in feelings of discomfort and confusion. Therefore, neither society or myself is able to fit me neatly inside a category. I experience unwelcoming challenges and feelings because of the intersections of other aspects of my identity with being Salvadoran.

Overall, my Salvadoran identity helps to shape who I am, as well as my feelings toward society itself. This is a two-way street, as society’s treatment of me changes based on how I am perceived. I experience societal backlash when I fail to meet the societal expectations of both a White woman as well as a Salvadoran individual. Because of my hybridity and skin color, I cannot be neatly categorized in society, which produces unease, both for society and myself. The language creates barriers between myself and Salvadoran culture, which create feelings of discomfort. RIS adds to this discomfort, demonstrating how I am not connected to my Salvadoran culture. Gloria Anzaldúa guides me as I connect my race to my identity and consider how intersectionality is intertwined to argue how my race is the most salient aspect of my identity.

Sources

Anzaldúa, Gloria. “How To Tame a Wild Tongue.” Borderlands: La Frontera: The New Mestiza.

San Francisco: Aunt Lute Press. 1987. 53-64.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. “La Conciencia de la Mestiza: Toward a New Consciousness.” Borderlands:

La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Press. 1987. 77-91.

Davis, James F. Who is Black? One Nation’s Definition. PBS, 2014,

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/jefferson/mixed/onedrop.html.

Haney López, Ian F. “The Social Construction of Race.” Critical Race Theory:The Cutting

Edge.

Hankivsky, Olena. Intersectionality 101. Researchgate.net, Sept 2014,

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279293665_Intersectionality_101.

Hybridity. Oxford University Press, 2023,

https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095952517.

Lacey, Sajni. Racial Imposter Syndrome, White Presenting, and Burnout in the One-Shot

Classroom. College and Research Libraries, 2022, https://crl.acrl.org/index.php/crl/article/view/25587/33494#.

Matsuoka, Karen. Trying to Understand My Japanese-American Identity. Blogger.com, Dec

2023, https://kmatsuoka.blogspot.com/2023/12/202312final-paper.html.

By Hannah Rivera

Themes: hybridity, essentialism, intersectionality, social construction of race

Comments

Post a Comment